For myself, I always write about Dublin, because if I can get to the heart of Dublin I can get to the heart of all the cities of the world. In the particular is contained the universal.

—James Joyce

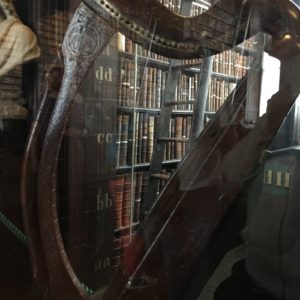

Ireland has one of the oldest vernacular literatures in western Europe, flourishing since the arrival of Christianity in the fifth century. An adaptation of the Latin alphabet into the Irish language supplanted the simple ogham writing system and catalyzed the rise of a small literate class during the Irish Middle Ages. The work of the monastery scriptoriums transformed Biblical texts into gorgeous works of art, culminating in what is considered the national treasure of Ireland, the Book of Kells, on display in Trinity College and one of the most visited pieces of art in the world. We made our own pilgrimage to view the book, along with other treasures, such as Brian Boru’s harp, in the Long Room. I’d actually seen the Book of Kells back in 1973, when the Met in New York hosted the “Treasures of Early Irish Art” exhibit. It was nice to see it again, even trapped in its glass case in very low light, with no photos allowed. I include a scan of the famous “Chi Rho” page from my vintage exhibit catalog. If you have never seen the lovely animated film, The Story of Kells, stop right now and watch this video, to give you a greater appreciation of the enormity of artistry on this page alone.

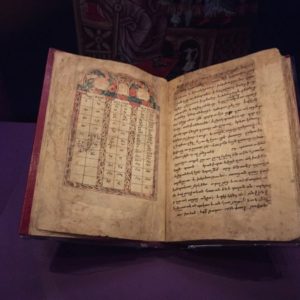

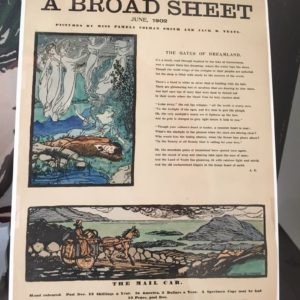

We found more rare books and manuscripts (clay tablets, Egyptian papyrus, Tibetan Buddhist scrolls, medieval Books of Hours …) in the impressive Chester Beatty Library collection. On a more contemporary note, the Dublin Library features an extensive exhibit on The Life and Works of William Butler Yeats (Flash-driven online exhibition available on their web site). Under English rule, starting in the Norman period with reverberations lasting to the present day, the Irish language was supressed and education in general was antipathic to anything that smelled of Irish culture. The mid-19th century Irish Literary Revival (or Celtic Twilight), a period of revival of interest in the country’s Gaelic heritage, is associated with the growth of Irish nationalism. The primary literary force for the movement is attributed to the efforts of Yeats and his collaborator Lady Gregory, who founded literary societies and the Abbey Theatre and edited collections of Irish fairy and folk tales.

A Literary Gallery

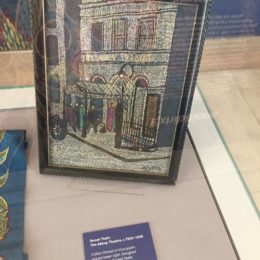

I arrived in Dublin (after a short layover in Manchester) the same afternoon our tour group met up, so I added a few days at the end of the tour to return to Dublin and have more time to explore. I chose the Castle Hotel across the Liffey, but the distance back to the Dublin town centre was easily walkable. I especially wanted to visit the William Butler Yeats exhibit at the National Library, which was extensive and nicely designed. Close by was the National Gallery, home of a few other members of the Yeats clan, including painter Jack Yeats (whose The Liffey Swim won the Irish Free State’s first Olympic medal, in 1924, a silver) and sisters Lily and Lolly, who were involved in establishing the Dun Emer Guild, whose purpose was to provide employment for women, to improve art and design generally, to promote the production of Irish goods and develop Irish culture, to promote all things Irish, including the language. Ireland’s most popular painting (yes, it’s official), Hellelil and Hildebrand, the Meeting on the Turret Stairs by Frederic William Burton, was sadly not in display, but a very knowledgeable gallery guard directed me to the resident Caravaggio (The Taking of Christ, mouldering away on a Jesuit Brothers dining room wall until it was discovered in 1990 and moved here) and we had a lovely chat about the Newgrange burial mounds.

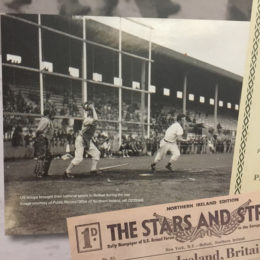

The hoard of treasures in The National Museum of Ireland – Archaeology is pretty much overwhelming, with the really good stuff tucked into the Treasury. Many of these items had traveled to New York City for the 1973 exhibit, but I still spent a lot of time gawking at all of that gold and Celtic interlace design. Somehow still not completely exhausted from all that culture, Dorothy and I headed across the river to EPIC: The Museum of Emigration, a fully digital exhibit housed in a nineteenth century tobacco, tea and spirits warehouse along Custom House Quay. 1,500 years of Irish history and culture in a series of state-of-the-art interactive galleries: they even give you a passport to stamp after you’ve survived each room’s quizzes. This museum would be especially great for kids (and if you drop Rick Steves’ name there is a considerable discount, just saying …), but after our visit we were sincerely exhausted and in need of a drink. Fortunately, the Harbourmaster Bar & Restaurant was only a block away.

Museum Gallery

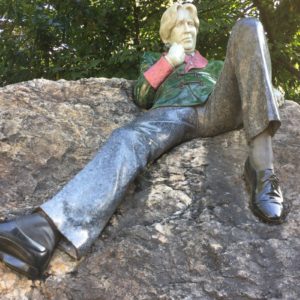

Dublin is infused with its political history and celebrates the men and women who have championed Ireland’s fight for independence. (Irish political history is way beyond the scope of this travelogue: find a good book!) Strolling through Stephens Green, one finds statues to Wolfe Tone, Constance Markievicz and W.B. Yeats; Merrion Square includes a bust of Michael Collins, and I walked past an imposing statue of Charles Stewart Parnell each time I strolled down O’Connell Street (yes, there’s also a statue of Daniel O’Connell on the street that bears his name). My hotel was across the street from the Garden of Remembrance in Parnell Square, a lovely small park that features a sculpture of the Children of Lir of Celtic mythology. Close by is the GPO, headquarters of the men and women who took part in the 1916 Easter Rising. Still a working post office, the site includes the GPO Witness History immersive exhibit with original artifacts, video footage, and information about the rebellion. There are still a few bullet holes in the building’s columns, and a bronze statue of the Dying Cúchulainn stands in the front window (where, unfortunately, it is difficult to view or photograph).

Political Gallery