Out of Ireland have we come.

Great hatred, little room,

Maimed us at the start.

I carry from my mother’s womb

A fanatic heart.

Drumcliffe

Our last stop before crossing the border into Northern Ireland was at Drumcliffe in County Sligo, the site of a monastery founded by St. Colmcille in the 6th century. Today, below Ben Bulben Mountain, a 19th century church is nestled adjacent the ancient graveyard, which contains an outstanding 11th century sandstone Celtic cross and the grave of poet William Butler Yeats. Yeats loved this area and requested burial here, with the instructions that the grave consist of “no marble, no conventional phrase.” His gravestone is fittingly inscribed with lines from his poem “Under Ben Bulben.”

The pastor at St. Columba’s Church was happy to talk with us about the rich history of this site and the achievements of one of Ireland’s three patron saints. Born in 521 into a branch of the O’Neills and christened Crimhthann (meaning “Fox”), his mother was a princess of Leinster and his father descended from Niall of the Nine Hostages: definitely a royal lineage. During the young man’s fosterage and education, he found his religious vocation and new name (Colmcille: “Dove of the Church”). Colmcille’s monastic career was not a quiet one: he traveled widely, founding churches and monasteries and impressed many people with his wisdom and faith; but he also got into a dispute over the ownership of a manuscript copy, and his involvement in (sometimes bloody) Irish clan politics displeased his religious contemporaries. More or less in exile, Colmcille and a small group of followers then sailed to Scotland, where he founded a monastery on Iona, whose scriptorium became an important center of learning and one of the greatest workshops for creating illuminated manuscripts. Work on the Book of Kells may have begun on Iona before the threat of Viking invasion resulted in its being transported to the Irish center in Kells. During his final years on Iona, Colmcille helped negotiate harmonious relations between the Scots and the Picts, and is even said to have encountered (and commanded) the Loch Ness monster. Surely a man of many talents!

In the Ulster dialect (particularly around Belfast), Northern Ireland is pronounced with two syllables and this has become an affectionate nickname for the country, proudly displayed on bumper stickers and football jerseys.

Our first stop once we crossed the border into Northern Ireland (which can be spotted by the discerning eye by the change from speed limit postings in km/hour to mph) was a brief afternoon visit to the border town of Derry/Londonderry (depending on your political bent). The second largest city in Norn Iron, Derry is famous for having Ireland’s only surviving, and mostly intact, city wall. Built 1613–1619 under the supervision of The Honourable The Irish Society, a consortium of a dozen wealthy London guilds which still owns the wall, its purpose was fortification of the city during the period of plantation: settling Protestants from Scotland and England in the surrounding county and displacing the local Catholic population to the rocky boglands. Derry became an major port of emigrationn during the mid-1800s, a key escort base for U.S. convoys heading to Britain during World War II, and the site of surrender of 60 surviving German U-boats at the end of the war.

Political and religious tensions going back to the 17th century led ultimately to Derry becoming a center of conflict during the “Troubles” and culminating in the ugly events of Bloody Sunday. On January 30, 1972, 10,000 people protesting internment without trial marched through the Bogland area, with 14 protestors killed by British Army troops. Although Derry is now peaceful with a 70% Catholic population, the events of this turbulent period are memorialized in the twelve Bogside murals, which can be seen even from the city wall. A powerful sculpture by local teacher Maurice Herron, titled “Hands Across the Divide,” is located near the Craigavon Bridge, and in 2011 the lovely curving pedestrian Peace Bridge crossing the River Foyle became an integral part of the city’s infrastructure, with many locals using it daily. In 2010, after a 12 year investigation that found the protestors innocent, British Prime Minister David Cameron formally apologized to the citizens of Derry for the events of Bloody Sunday.

Before we took an excellent guided walking tour of the Derry city wall, we were able to wander through the Neo-Gothic Guild Hall (built in 1890, destroyed in in a 1913 fire and rebuilt, and again damaged by the IRA in 1972), and stroll across the Peace Bridge to appreciate a view of the city centre from the east bank of the River Foyle.

Then it was on to Portrush, our first overnight stay in the north and conveniently situated for visits to sites along the Antrim coast. Once known as the “Brighton of the North,” Portrush is a slightly past-its-prime seaside resort, with lowbrow amusement arcades and recreation sites that attract local families on the weekends and students on break. It reminded me of some of the slightly worn out towns down the New Jersey shore. (In my birth state, you go “down the shore,” not “to the beach”—aspiring authors of the next Mafia blockbuster take note.) Our group dinner the first evening was the only mediocre meal I recall from the trip; fortunately, we followed that up with an excellent dinner the next night in the bustling Harbour Bar & Bistro (waits of over an hour, but available seating at the bar: yes, please!)

Day trips from our Portrush hub included a visit to the Giant’s Causeway, Norn Iron’s only UNESCO heritage site. The landscape of thousands of interlocking basalt columns resulted from an ancient volcanic fissure eruption, but I prefer the mythological explanation: a rivalry between Irish giant Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn MacCool) and Scots giant Benandonner. Hollering insults across the Sea of Moyle (the two countries are only twelve miles apart here), a trial of strength is challenged and Finn builds a rock bridge so his rival can cross. Exhausted by his labors, Finn is asleep when Benandonner shows up for the fight, and Finn’s wife Oonagh sees that the much larger giant will easily beat her husband. So she dresses him in baby clothes, and cautions Benandonner not to wake her sleeping bairn. Peering in, the Scots giant marvels at the size of this baby and calculates how large Finn must be … and then hurries back home, destroying the causeway in his haste.

The Antrim Coast

I probably took more photos at the Giants Causeway than anywhere else on my trip: what a fantastic landscape! With plenty of time to climb over the hexagonal rocks, or climb up for the view from above, it was a lovely morning’s excursion. Afterwards, we needed a wee dram, and headed to Bushmill Distillery for a tour and lunch. After fueling up, we explored more of the Antrim coast, including a tour of the picturesque ruins of Dunluce Castle. Built around 1500, the castle had a tumultuous history as the site changed hands via political upheavings, from the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, through Cromwell’s ascension to power, to the Restoration of Charles II. In 1928 the site came into state guardianship and is maintained by the Department of Communities, HIstoric Environment Division. The printed brochure and knowledgable guides (ours vied for the privilege of leading our group: thanks, Rick!) are both excellent, and the view was magnificent. One can see the appeal to the MacQuillan and MacDonald clan owners, despite the winter storms, legends of banshees, and the kitchen falling into the sea, reputedly during a banquet.

Belfast

Our final tour stop was in Belfast, Norn Iron’s largest and capital city. On a site occupied from the Stone Age, the remains of Iron Age forts have been found near the city centre, and a castle built in the 12th century seems to have survived until the early 1600s. Belfast’s modern period began in 1611 when Baron Arthur Chichester encouraged the growth of the town, and by the end of the 17th century Belfast was not only a busy port but one of the greatest linen centres in the world. Shipbuilding became established during the Industrial Revolution, but, severely damaged during World War II, Belfast’s manufacturing activities declined through the 1970s, and these sectors have been replaced by service industries, food processing, and machinery manufacture.

In 1888, Queen Victoria granted Belfast city status, and a grand and magnificent building was immediately planned to display this new honor. Designed by Alfred Brumwell Thomas in the Baroque Revival style, Belfast City Hall opened in 1906. Free guided tours are available, but we just wandered around freely after a morning walking tour of the city centre area. The building is impressive, with its facade of Portland stone, dozens of beautiful stained glass windows, some original to the building and more added to commemorate historic events, which document Irish history from the Tain Bo Cuilange to the 2006 City Hall centenary. The east wing contains an extensive 16-room exhibition of city history, with the Bobbin Coffee Shop in the midst of the display: a nice place for a quick lunch. A huge statue of Queen Victoria dominates the front entrance to City Hall, but there are over a dozen memorials and sculptures dotting the manicured lawns. Most important to me was the USA Expeditionary Forces Memorial, a marble column marking the landing of the first US forces in Europe (including my father) during World War II.

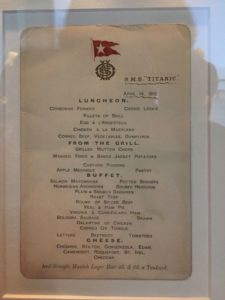

Titanic Belfast, opened in 2012 to commemorate the centenary of the ship’s launch and sinking, is the most visited attraction in Belfast. It’s huge, well-organized and comprehensive, and pretty much deserves the hype. Located on the site of the former Harland & Wolff shipyard in the city’s Titanic Quarter, the nine gallery interactive museum is a monument to Belfast’s maritime heritage, its star shape evoking the White Star Line logo.. There are gantry rides, an underwater cinema show, stunning cabin recreations with holographic dialogues, posters and costumes from films about the disaster, and some actual artifacts from the White Star Line. You can also walk the slipways where the Titanic and Olympic were built, gawk at Samson and Goliath, the enormous twin cranes that are landmark structures of the Belfast skyline, and take a break on one of the wooden benches set in Morse code patterns around the building.

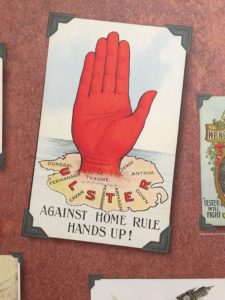

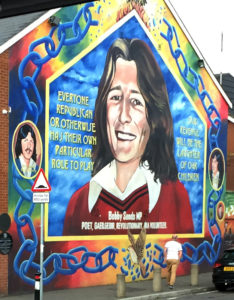

Among other important Belfast attractions are the “peace walls” from the turbulent history of Ireland’s Troubles. The first of these walls was built in 1969 to minimize the violent interactions between Catholics (most of whom were nationalists who identified as Irish) and Protestants (most of whom were unionists who identified as British). Initially designed to be temporary, the walls instead spread, and even after the Belfast Good Friday Agreement of 1998 officially ended the period of the Troubles, around 21 miles of walls remain in Northern Ireland, some as high as 25 feet, still separating Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods. The most famous of the 40 Belfast peace walls divides the Falls and Shankill Roads in the western part of Belfast, separating suburbs that are either nationalist or unionist, and are covered with murals and graffiti that depict the history and politics of the conflict. An “International Wall” on the Falls Road side focuses on environmental issues and human rights activism around the world. Black Taxi tours are a popular tourist activity, with local drivers who will take visitors to view the highlights of the walls and their murals and graffiti, and explain the cultural, religious, and political significance of each site. We had a bus tour of several of the wall neighborhoods, but this would be well worth a longer visit on a return trip to Belfast. The Northern Ireland government wants to remove all of the walls by 2023, but there is still enough political tension in these neighborhoods to resist this change and it may take another generation, or more, to convert the walls from physical to purely symbolic historical memorials.

We stayed at the Europa Hotel, built in 1971 on the site of the former Great Northern Railway Station. The Europa has the dubious distinction of being known as the “most bombed hotel in Europe” from its central location housing journalists covering the events of the Irish Troubles (although damaged during 36 bombings, it was never closed or totally destroyed). Our stay was explosion-free and the staff were charming and efficient. Our farewell dinner was held at Coco, an excellent bistro a short walk away, and though many of us peeked into the historic Crown Bar across the street, we spent the evening hoisting goodbye toasts in the Europa’s Lobby Bar. And then to bed, after packing for a morning bus ride back to Dublin to finish my visit.